The Origins of Second-Order Conflict is Part 2 of Unlocking the Hidden Value of Conflict

The root cause of second-order conflict is poor management of first-order conflict. Here are the primary reasons organizations fail to manage first-order conflict successfully:

1. Conflict Avoidance Mindset

Humans have been socially conditioned to avoid conflict and protect group harmony, or at least the illusion of group harmony. An ability to form groups of likeminded people and collaborate is part of what has made the human species so successful. Survival and success as individuals is based on the survival and success of the groups we belong to and contribute to. Business is one of those groups. As in society, people working within companies see conflict as something bad for cohesion and harmony. We’re told to get things done and get along while doing it: Don’t rock the boat, mind our own business, etc.

For most people, the word “conflict” itself suggests arguments, confrontation, and fighting, escalating up to full-scale war. Even the words we use when discussing conflict reveal how we view conflict socially: We talk about people taking and defending positions, attacking weak points, and shooting down ideas. Engaging in conflict with our group/company can be very risky to our status within the group/company. At the extreme, if we engage in too much conflict, we risk being exiled from the group, e.g. passed over for promotion, left out of meetings and off committees, or fired. The result is a mindset that we are better off if we avoid conflict. However, when we avoid first-order conflict, we generate second-order conflict, which is much harder to handle.

2. Misaligned Incentives

One of the great challenges of managing any type of group endeavor is balancing group versus individual accountability. We want the group to succeed, and we also want to make sure everyone is pulling their weight. As a result, there is a strong tendency to try to unbundle group objectives into individual objectives. At face value, this isn’t the worst idea, and may even seem logical. Still, there are two significant flaws with this approach that can derail a group’s ability to effectively process first-order conflict: First, it drives divergence of objectives that can make conflict resolution very difficult. If everyone is trying to get to a different destination, how can we possibly agree on the method to get there? Second, it forces conflicts to become win-lose propositions by blocking the give-and-take discussions that would typically lead to win-win solutions. Misalignment of incentives is a surefire recipe for creating second-order conflict, as there is no single option that meets the nuanced needs of all involved parties.

3. Inadequate Communication

Contrary to our perceptions, humans do not effectively communicate with one another. Even the most skillful communicators share the minutest fraction of what they are actually thinking. Further, people on the receiving end of communication retain a small percentage of what they hear. This gap between what one person communicates and what the other person hears results in a fragment of what someone is thinking actually being absorbed by the other. The problem worsens when communicating with close associates and other familiars: Culturally, we experience something called “close communications bias,” which means we assume other people close to us–like our team–already know what we know. The result is we communicate even less. This assumption makes resolving conflicts challenging because our starting point is already a misunderstanding.

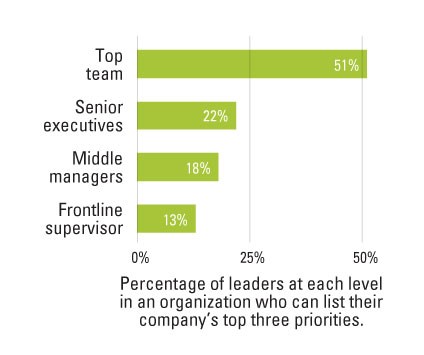

It is astounding how pervasive and severe this communication problem is: In fact, an MIT Sloan School of Management survey illustrates perfectly the magnitude of this particular stripe of misunderstanding. In it, 4,012 executives, managers, and supervisors across 124 companies were surveyed. It was discovered that only 51% of top team members could accurately list their company’s top three priorities. At the middle manager level, only 18% of managers could list their company’s top three priorities. With this level of confusion, disagreements and missed expectations are the norm. It should come as no surprise that second-order conflicts are an enormous problem when you consider the inadequacy of our communication.

MIT Sloan Management Review February 12, 2018

4. Jumping to Mistaken Conclusions

A remarkable feature of the human mind is our ability to fill in the gaps. While we may only receive a small fraction of the information communicated to us, our minds insert any missing details. We use our prior experiences and imagination to extrapolate from limited data. This ability to fill in the gaps creates the illusion that we communicate well and understand each other. When we extrapolate from limited communication to explain disagreement, most of us fall into the trap of attributing actions to imagined bad intentions that may not exist in reality. In fact, imagined explanations can often be way off the mark and destroy trust, do significant damage to interpersonal relationships, and lead to the emotional escalation of conflict.

This ability to fill in the gaps by extrapolating also affects how we view data. Our minds seek coherence between our mental narrative and objective data. To create this coherence, our subconscious cognitive biases amplify data and analysis that agrees with our mental narrative and discounts data and analysis that does not. The conflict is not about the data, it’s about the differences in our mental narratives and the differing conclusions those narratives drive. This, in part, explains why getting more data is not always helpful.

5. Dysfunctional Behaviors

When we do engage in conflict, our skills for managing conflict are generally not up to the task. Most of us have had very little, if any, training in effective conflict management. The training we do receive is focused on team building, developing superficial trust, and simply being polite and friendly to each other. Most people don’t have the skills required to engage in constructive conflict. Without well-developed skills, people resort to primitive behaviors such as dominance and passive-aggressiveness, which are both widespread and can lead to high levels of unhealthy second-order conflict and failed team relationships.

While there are countless types of behaviors that can cause second-order conflict, the three most common are delegating conflict, passive-aggressiveness, and bullying: Delegating conflict happens when leaders act like conflict doesn’t exist or make decisions that are so ambiguous, nobody is sure which choice was decided upon. The most common version of this is a failure to prioritize accompanied by some vague statement about how all of our top initiatives are top priorities. When this happens, conflict gets delegated down the organization into the hands of less capable and less knowledgeable people who are then forced to deal with a mess. Passive-aggressive behavior can be debilitating to organizations. This is no truer than when executives communicate and act as if they agree, but then subtly undermine any progress. In large and risk-averse organizations, this type of behavior can be widespread and difficult to counteract, turning first-order conflict into second-order conflict with great efficiency.

In most well-run organizations, overt bullying has become socially unacceptable. That said, covert bullying is still commonplace, whereby a person shuts down information-sharing and tries to force decisions in ways that leave others angry and hurt. Left unchecked, this behavior drives up the level of second-order conflict quite quickly.

The Origins of Second-Order Conflict is Part 2 of Unlocking the Hidden Value of Conflict

Unlocking the Hidden Value of Conflict

Unlocking the Hidden Value of Conflict